As an active duty military chaplain, I get to work very closely with chaplains of various Protestant denominations, and I count several of them among my good friends. In fact, I’ve always seen it as a sign that a solid friendship has developed when we’re able to poke fun at each other’s religions – always good natured and completely in jest, of course. One of my favorite ways to give my evangelical Protestant chaplain friends a hard time is after they finish one of those long-winded, off-the-cuff prayers in which they “just” pray for several things (e.g., “Lord, we just pray that You’d bless us…and Lord we just want to worship You today…and Lord we just come to You to just ask You to just heal this person…”). Anyone who has an evangelical Protestant friend knows exactly what I’m talking about, and as I’m quick to point out to such chaplain friends of mine, you can’t just pray for multiple things: either you pray for many things or you pray for just one thing, but it’s both logically and grammatically incorrect to just pray for multiple things. As many have pointed out, the frequent repetition of “Lord, we just…” sounds like they’re praying to the “Lord Wejus” instead of the Lord Jesus!

This past Sunday, December 27th, my Christmas spirit was slightly crushed by the realization that I wouldn’t be able to fully celebrate my patronal feast, the Feast of St. John the Apostle, given that it fell on a Sunday this year. As most practicing Catholics know, Sundays usually trump any other feasts days, and that’s definitely the case with the Sunday after Christmas. In the so-called Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite (which is what 90% of the Catholics in the world celebrate), the Sunday after Christmas is reserved for the Feast of the Holy Family, and even in the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite (which is the version of the Roman Rite that existed immediately before the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council), the Sunday after Christmas has its own special liturgy that similarly trumps whichever saint’s feast happens to fall on that day.

This unfortunate convergence of my patronal feast with a big ol’ Sunday got me thinking about how the liturgical calendar during the Christmas Season has changed significantly in just the last century. My patronal feast actually used to be a whole week long (what we call an “octave” since it was celebrated for a full eight days) and it didn’t matter what day of the week it fell on – even be it a Sunday – it was still celebrated! In fact, that was the case with several other feasts, too, but as I’ll speculate why below, Pope Pius X didn’t like this. So, in 1911 – decades before the additional liturgical reforms of Pope Pius XII and then later of the Second Vatican Council – he decided to reduce several octaves, including three that used to be celebrated during the Christmas Season, namely the Octaves of St. Stephen the Protomartyr (Dec 26 – Jan 2), of St. John the Apostle (Dec 27 – Jan 3), and of the Holy Innocents (Dec 28 – Jan 4). Such feasts would thenceforth only be celebrated as “simple octaves,” meaning on just the first and last day of the octaves.

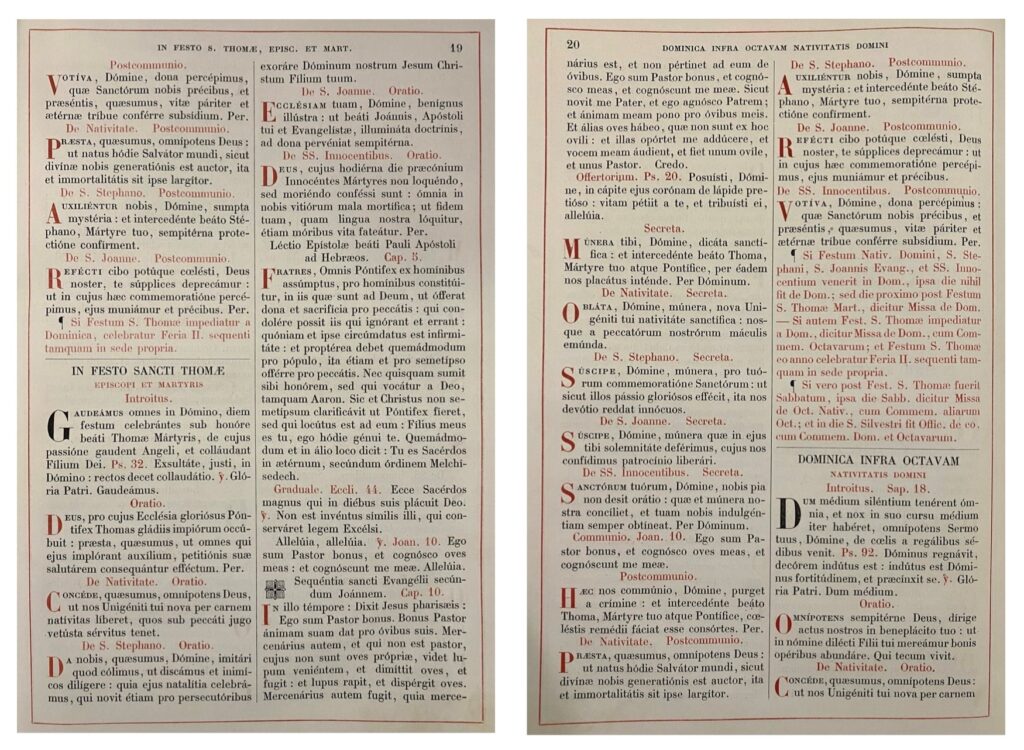

Back to my evangelical Protestant chaplain friends who pray to the Lord Wejus (I love you guys!) … if you happen to find a Roman Missal printed before the Pian liturgical reforms of 1911, and if you happen to flip to the Feast of St. Thomas Becket (celebrated on December 29th), you’ll notice that it has a total of five mandatory prayers for each of the three presidential prayers (the collect, the prayer over the gifts, and the post-Communion). That’s 15 proper prayers for that single day, and if you do it correctly, you’ll sound a lot like an evangelical Protestant praying for just several things: first for St. Thomas’ intercession, then for the grace of Christmas, then also for the intercession of St. Stephen, oh and also for St. John’s intercession, and finally also for that of the Holy Innocents, and then go through that entire list two more times during the Mass. You see, while December 29th was the Feast of St. Thomas Becket, it was also within the Octave of Christmas, and the Octave of St. Stephen, and the Octave of St. John, and the Octave of the Holy Innocents, and so we really had to mention all those other guys too lest we disrespect their octave feasts.

Understandably, Pius X didn’t want his priests to sound like evangelical Protestant chaplains (I’m quite sure that wasn’t his thinking but I like to think it was), and so, as above, he reduced these octaves to “simple octaves.” 44 years later, in 1955, Pius XII abolished all octaves, save those of Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost; and then the Second Vatican Council, a decade later, abolished even the Octave of Pentecost. Technically, the Octaves of Christmas and Easter still exist today, even in the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite surprisingly, although most Catholics nowadays – through no fault of their own – have never even heard the term “octave” and probably wouldn’t recognize the liturgies of January 1st or of the Sunday after Easter as being the “octave day” of those major feasts. As for the issue of December 29th, when a priest celebrates the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite now, he only mentions St. Thomas Becket and the Octave of Christmas; and in the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite, it’s even worse: no mention of Christmas anywhere in the Mass, just St. Thomas. “Ho Ho Ho?” More like “Ho Ho No!”

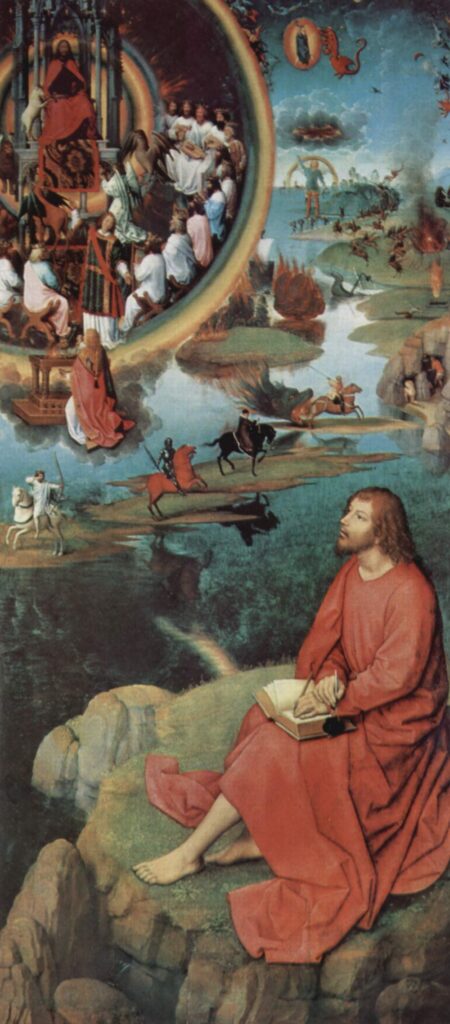

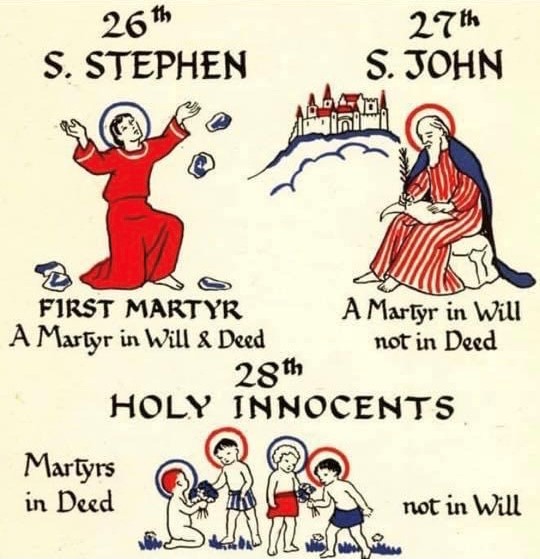

I like what Pius X was trying to do, but I think we need to bring back the Octaves of St. Stephen, St. John, and the Holy Innocents. I’ll let the liturgical experts debate what that should look like on a rubrical level, but my argument here is simply that there is great value and meaning in those three feast days, and that they should therefore be more broadly present throughout the Christmas Season and, indeed, the life of the Christian. Think about it: why are those three feasts celebrated on December 26th, 27th, and 28th, respectively? It’s certainly not because there’s any historical evidence that those saints died on those days, as is usually the norm for determining a saint’s feast day. Traditionally, the saints honored on these three days are collectively known as “Comites Christi” (“Companions of Christ”), and are placed on the liturgical calendar intentionally: they each speak to the martyrdom – that is, the “witness” – that we are all called to give to the newborn Lord. Some of us, like St. John, are called to witness to the Lord in word but not in blood (he was the only apostle not to be martyred); some of us, like the Holy Innocents, are called to witness to the Lord in blood but not in word (they were all too young even to speak); and some of us, like St. Stephen, are called to witness to the Lord in both word and in blood. The fact of the matter, however, is that every single human being is called to witness to the Lord in one of those three ways, without exception. Red martyrdom, white martyrdom, it doesn’t matter: we’re all called to be martyrs.

Wouldn’t it be completely appropriate, then, for the full octaves of these saints – and not just a single day – to be celebrated during the Christmas Season? It seems all the more urgent in a society such as ours which has so secularized the birth of our Lord to the point of barely seeing the demands of His birth on our lives. I, for one, think that the Christmas Season would begin to experience a much-needed shift if we were constantly reminded – for eight solid days – that this cute little Baby Boy Whose birth we celebrate is expecting each and every one of us to witness to Him in the manner of either St. Stephen, St. John, or the Holy Innocents. As above, I’d want to leave it to the liturgical experts to determine what that actually looks like in our sacred liturgy, but there’s got to be a way to avoid sounding like evangelical Protestant chaplains while more broadly celebrating the unique contributions of those who, in varied ways, were among the first to witness to our Lord.

(A previous version of this post incorrectly asserted that it was Pope Pius XII who reduced the Comites Christi octaves to simple octaves. Thanks to the Facebook page “Restore the ’54” for correcting me!)